A Second Shot for Both Brands

“Diageo sells portfolio of brands to Sazerac,” read the headline of the press release. It went on to say that among the brands acquired were Seagram’s VO and VO Gold. I found this fascinating on a number of levels. First, you might say that these brands have seen better days and why would a company like Sazerac, with a full and lush portfolio, want these brands. On the other hand, Sazerac has done amazing things with brands they acquired from Seagram (think Eagle Rare and Fireball to name only two) so, a revival of the Seagram VO franchise would not be unusual or impossible.

It was under my watch at Seagram that VO’s decline accelerated and VO Gold was created. So, among others, I contacted John Hartrey and Art Peterson (both of whom you have met before on this blog) who played important roles with those brands, back in the day. I also spoke with Drew Mayville, who worked on the creation of VO Gold and was the 4th and last Master Blender at Seagram, and is now the Master Blender at Sazerac.

{By the way, as I write this, I’ve learned that Sazerac has introduced “Mister Sam” Whiskey — a Blend of Sazerac’s American and Canadian Whiskeys and a tribute to the Seagram founder, Sam Bronfman. The blend was created by Drew Mayville.}

The importance of VO to Seagram

The importance of VO to Seagram

Let’s start with the fact that the New York Stock Exchange symbol for Seagram was VO. That speaks volumes. Next, consider the fact that The Chairman (aka Edgar M. Bronfman) earned his stripes at the company working on VO.

It was always a great whiskey, a 6-year-old Canadian blend and the aspiration of Seagram 7 drinkers looking for more and, yes, better.

I recall, after taking over the position of U.S. marketing head, being summoned to a lunch with The Chairman in his private dining room. This was during the time that Edgar Jr was involved in Hollywood. I think, in retrospect, the purpose was to let me know that he was back in control and was in charge during this interregnum. Really? As though I didn’t know? All I recall from that lunch was that the butler asked me what I wanted to drink and I looked at him in amazement. With the exception of a special occasion, drinking at lunch was not for me. When I told him so, his look was beyond amazement as he said, “The Chairman generally has a VO before lunch… I’d suggest you do the same.”

Some believe that the term VO stood for “Very Own” and, according to the Master of Malt website, “It is said the blend was created after a post-prandial conversation (during or relating to the period after dinner or lunch) amongst the Seagram family; the letters “VO” might well stand for “very own”, as in, their very own blend…”

Art Peterson told me the following story about the family’s commitment to VO:

“When Edgar Senior and Charles (Bronfman) were running the Canadian operation, they learned that due to some production or maturation difficulties, the blenders were unable to match the character of the current VO production to the standard. So, Charles and Edgar made the decision to stop shipping the brand until they solved the problem. That meant that there were shortages in the marketplace, but they were determined that no shipments would be made until that problem was solved.” (Despite my griping about the owners, they were all about quality and doing the right product thing, no matter what.)

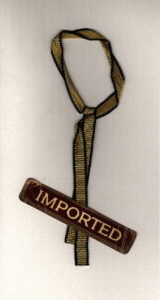

Most interesting to the VO story is the packaging, notably the ribbon on the bottle. I’ve been told that it was the racing colors of a Bronfman owned horse. More about that ribbon in a moment.

But tastes changed and the brand slipped

By the early 1990s, consumer liquor preferences had leaned to clear spirits in general and vodka in particular, so whiskies (with a few exceptions) suffered volume declines. At Seagram, Seagram 7 Crown was huge and a bar staple so its losses were manageable. At the other end, Crown Royal, whose appeal was to top shelf drinkers and strong regional support, actually grew in volume. In part, this was a result of an upmarket line extension — Crown Royal Special Reserve. Seagram VO was awash in red ink and, while it held its own against the archrival Canadian Club, you didn’t want to be the brand manager who presented the sales and marketing results when there was a Bronfman in the room. As in… “our sales are way down BUT, our market share is up.”

The central question became, “What to do about VO.”

Enter the Consultants

The owners of Seagram loved to bring in consulting companies such as McKinsey or Boston Consulting Group — you know, highly paid outsiders who basically ask for your watch so they can tell you what time it is. I couldn’t help but wonder why they chose to go around the company’s employees. I often felt they thought, how smart can our people be, they chose to work for us didn’t they?

Among other things the consultant contribution to the brand was to “take the goodness away,” by eliminating what they saw as ‘unnecessary’ packaging elements. You know… what we in marketing and sales call “brand personality elements.” Among the cost saving victims was the VO ribbon.

The Answer…

…came from the toilers in the company, not the consultants. In so doing, we broke what classic marketers call the rule of line extensions — don’t line extend from a weak brand. Nonsense.

There were many reasons why an upmarket VO line extension made sense, including increased margin, additional VO facings in stores, a new face in the brand’s franchise and lineup, and more. And, the success of Crown Royal Special Reserve, gave us the impetus to try that tactic on VO. What did we have to lose?

So, VO Gold was born and, with the thumbing of our noses at the consultants, we put all the goodness in packaging back into VO Gold. Including the ribbon.

But the strength of the brand came from the blenders and the marketers. Here’s how Art Peterson described what happened with the product formulation:

“Drew Mayville was part of the team and in on the creation of the brand. What happened was that VO Gold was just an idea. We knew it had to be some kind of a premium VO, but true to VO characters. We started by discussing, ‘What could we do to improve VO?’ Well, one idea, of course, is you can use older whiskeys. We decided that we would focus on eight-year-old whiskeys. And then, ‘What can we do to VO to make it different but still recognizably VO?’ We decided to go with a whiskey that would be brighter. Also, some of the characteristics in VO that we liked were the fruity characteristics, and that came from having certain yeasts that we used in our rye whiskeys in the VO blend.”

The proof of the blenders’ success came in a letter to Art from Charles Bronfman:

“I have tasted VO Gold and it’s just fabulous!!! Best damn VO I have ever tasted, and as you know, I have tasted an awful lot of VO over the years. Nice going, my friend.”

What I especially enjoyed about Seagram was the team spirit and, in this case, how marketing worked hand in hand with the blenders and production to bring this brand to life.

Led by John Hartrey, the marketing folks came up with a totally unique idea; never done before but used by others afterward. They ran a program that centered on “meet the blender.”

What they did was communicate, through advertising and point of sale, a series of dinners in five different markets. It was a contest whereby “you and 20 of your friends” could win a dinner with Art Peterson, followed by an expert tasting with him. It was a huge success and VO Gold was on its way.

About that ribbon

John reminded me of a great story about the VO ribbon. It was removed because it required special equipment and was expensive to produce. Little did the geniuses at the consulting firm (or many of us) know that it played a role in the Viet Nam war. According to John:

“When we removed the ribbon, we got a letter from a Vietnam Vet asking why the ribbon was removed. He told us that during the war, the VO ribbon was referred to as a “short timers’ ribbon”. The idea was that when someone had a short time left on their tour (probably 30 days), he put the ribbon on his uniform so that everyone knew to protect him and get him home.”

The story was corroborated here.

# # #

Seagram’s VO and VO Gold now have a second shot at success. The best part is that one of the blenders who worked on the original products, Drew Mayville, is the current Master Blender for the new owners (Sazerac) of the brand.

Drew used a great expression when we spoke that really resonated with me, “A lot of companies want to meet consumer expectations. At Sazerac, we strive to delight the consumer.”

I can’t wait for it to come on the market.

Thank you John, Art and Drew for taking the time to talk with me about this.